Cheryl slid into her oversized chair and looked at the piles of papers on her desk. Only two hours left in the day, then she needed to finish packing and catch the flight for the hospital administrators conference.

At least she had finished creating the presentation she would be giving, tying in perfectly with the conference theme, "Making the Grade Through the Patient Experience." The concept was familiar territory for Cheryl.

Not only was her hospital facing increased competition from other area medical facilities for patients and revenue, but the overall patient experience—everything from the hospital environment to discharge information—was now evaluated publicly via results of the national Hospital Consumer Assessment of Healthcare Providers and Systems (HCAHPS) survey. A below average rating risked a hospital's reputation and revenue.

It was only a year ago that her hospital finalized the changes that brought about a new "patient-centric" environment. Such facility changes were increasingly the goal of hospitals nationwide seeking to meet competition. Patient satisfaction also became the focal point because it helped hospitals make the grade for Medicare reimbursement.

Gone were the stark white walls, shared patient rooms, and institutional waiting room furniture. In their places were private suites, contemporary decor, and walls painted warm, inviting hues displaying beautiful works of art.

Cheryl was looking forward to sharing some of the statistics on patient satisfaction. Just one thing nagged at the back of her mind. Reducing re-admissions had been an important goal of the "patient-centric" project and had an impact on Medicare reimbursement as well.

The problem was, she had not seen re-admissions drop so far. Maybe it just took more time, but she couldn't help but think something was missing. That's why she'd authorized the follow-up questionnaire a month ago, asking patients about their discharge experience and first weeks at home.

She logged in and began skimming patient comments. The majority of responses had given high marks to the hospital stay. The problems seemed to come after discharge. Patients expressed confusion over instructions, medication, and contacts.

Her mind wandered to the upcoming conference. She always looked forward to going through the conference folder the night before the event. It was one of the best-organized conferences she attended.

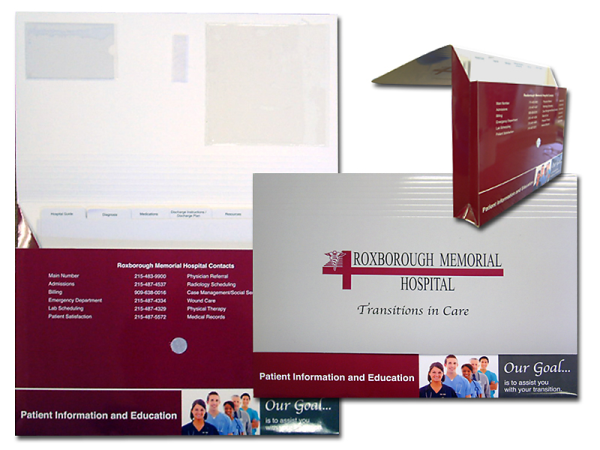

That's when the idea struck her. Patients weren't just looking for information, they needed to have that information organized for them, at their fingertips. If discharge information could be attractively presented, patients might be more diligent about following instructions once home. Re-admissions should decrease. In addition, the hospital's own brand could make a lasting, positive impression.

-resized-600.jpg)

Cheryl started making a few phone calls. By the end of the day, the ball was rolling on the hospital's new discharge kit containing the transition folder she had in mind.

At the conference a few days later, Cheryl concluded her presentation with an outline of the hospital's planned discharge folder, noting its anticipated marketing and financial payoffs. She noted the role of discharge information within the HCAHPS survey.

A year later, Cheryl made a return appearance as conference speaker. This time, she was able to discuss early evidence of lower patient re-admissions, likely stemming from improved discharge information. The discharge kit had gotten high marks from patients, while helping to keep the hospital's brand top-of-mind.